In India, trans and gender diverse persons face prejudice, violence, and social exclusion. As a result, some turn to begging and sex work, forms of survival that face criminal and societal sanctions. Despite the diverse tapestry of social identities in India, trans people are often seen only through the solitary lens of their gender. What gets especially neglected is their caste, a deep and indelible marker that cuts across all identities including gender. As a system of social segregation and oppression, caste underpins the Indian social fabric and justifies the subordination of and violence against those designated as ‘lower’ caste. Thankfully, this intersection – of caste and gender – is at the heart of a successful and ongoing endeavour.

Here is the backstory.

After a long struggle for recognition of their constitutional rights by Indian trans and gender diverse movements, in 2014, the Indian Supreme Court finally recognised the right to self determination of one’s gender, and the right to equality, dignity, liberty, non-discrimination, and autonomy of trans persons. Taking note of the socio-economic injustices faced by trans persons in India, the Court encouraged the Government to consider affirmative action in public education and jobs. Even as this verdict was widely celebrated across South Asia, it has not been complied with in its true spirit.

Finally, in 2019, the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill was introduced in Parliament. Drafted without any consultations with trans and gender diverse groups and activists, the Bill was criticised by trans groups, human rights, women’s rights and feminist groups because it lacked enforcement mechanisms as well we progressive features, recommended by the Supreme Court, such as affirmative action (commonly known as ‘reservations’).

In 2021, when the Government decided to extend reservations in public education and recruitment to trans persons, it included them in already existing reservations for the Other Backward Classes (OBC).

This submersion of reservations for trans people under another reserved category of the OBC did not fulfill the actual purpose of affirmative action. Trans folks belong to diverse caste groups such as the Scheduled Caste (SC), the Scheduled Tribe (ST), OBC, or even the dominant, upper caste bracket. However, this move of merging all trans persons would make them seem casteless and not account for the intersectional oppression they face. The discrimination faced by a trans person from an oppressed caste group differs vastly from that faced by a trans person from an oppressor caste group.

So, if the Bill was passed as is in the Parliament, then trans persons would have to compete with each other and with other candidates in the OBC category, going against the intention of inclusion. A trans person falling under the OBC category would stand to lose to other OBC candidates because of the former’s trans identity. An Scheduled Caste, the Scheduled Tribe, or Dalit* trans person would be forced to choose between their gender-based and caste-based reservation, possibly depriving them of a chance at greater visibility and voice.

For all these reasons, opposing the Bill became an urgent, human rights concern.

It was then that the India-based Trans Rights Now Collective (a partner of CREA, one of the members of the Count Me In! consortium) took up this mission. They aimed to (a) increase public awareness around the issue of caste discrimination faced by trans persons; (b) complicate blanket depictions of the trans ‘community’ and the Dalit ‘community’, and (c) oppose the ambiguous inclusion of all trans persons in the category of ‘Other Backward Classes’.

The Collective had a better, alternative proposition–reservations for trans persons as a separate category, across already-existing categories such as Scheduled Caste (SC), the Scheduled Tribe (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC). This interlocking model of ‘horizontal reservation’ (already in use for reservations for women and persons with disabilities) accounts for the intersections of discrimination faced by a community. In the case of trans persons, it would allow them to apply for reservation under the category of ‘transgender’ within each caste category, such as the SC, ST, or OBC category, if they meet such criteria. This would broaden their chances of securing educational and employment opportunities, without confining them to only one identity.

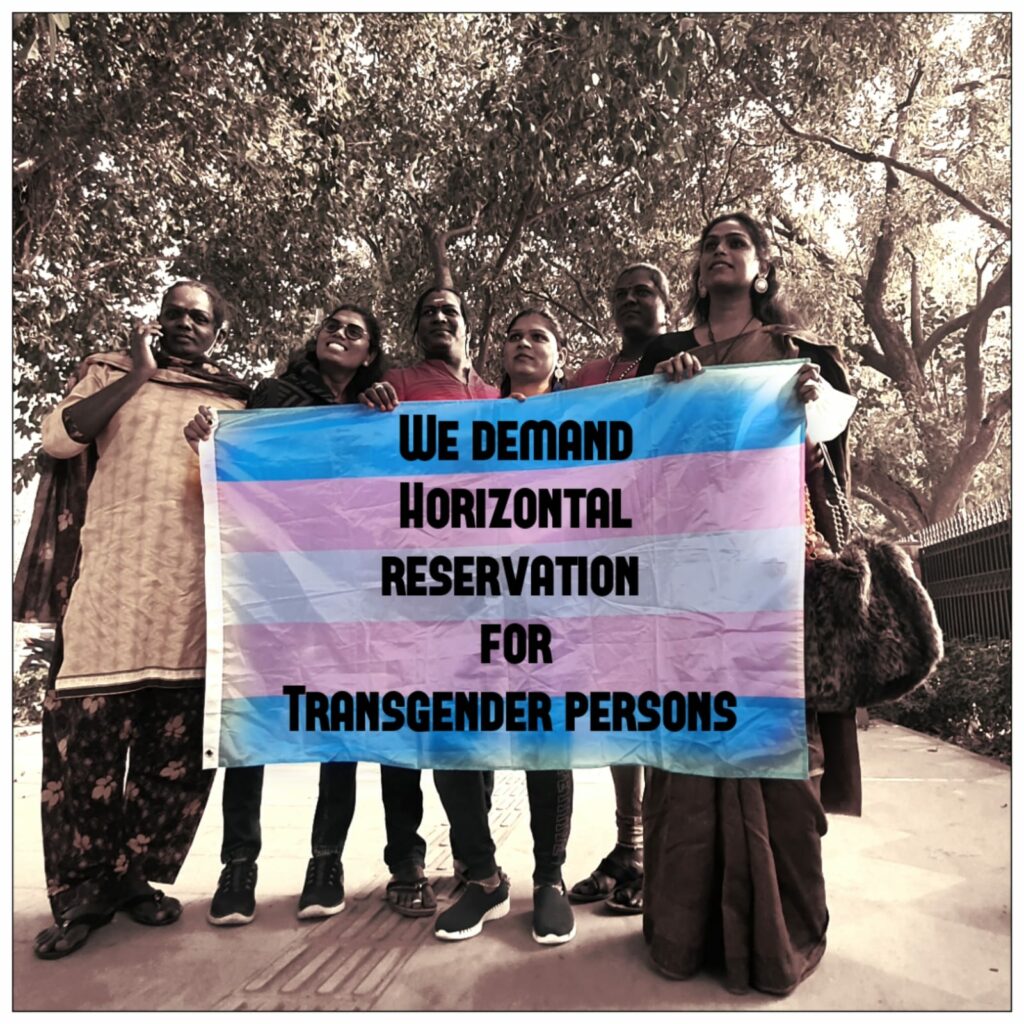

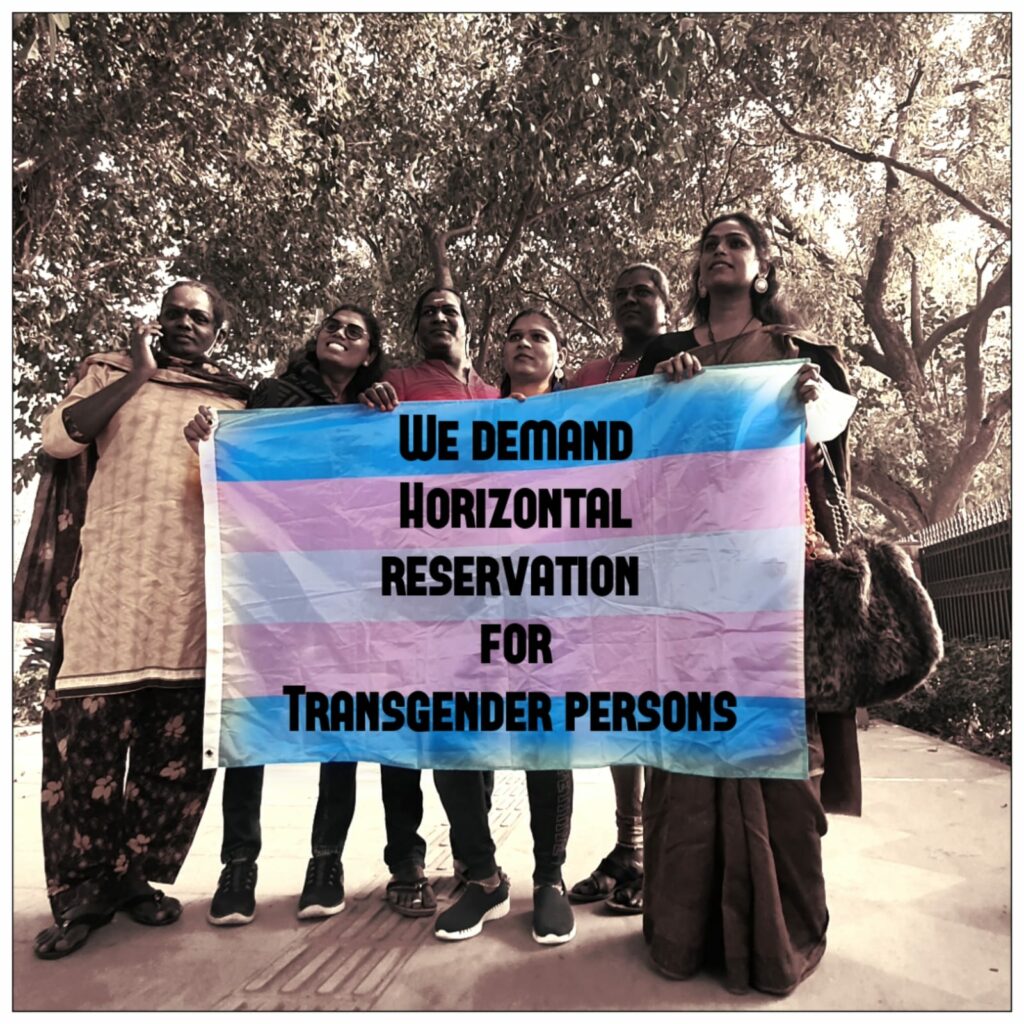

To highlight these concerns publicly, several members of the Trans Rights Now Collective and other trans groups held a Press Conference in Delhi. They also reached out to several Members of Parliament and Ministers with an informational brief. After intensive discussions on the status of Dalit trans persons, several politicians openly lent support to their demands on social media.

To support their advocacy, Trans Rights Now Collective also commissioned artwork that was widely shared by many vital stakeholders on social media. This sparked a public conversation on the intersectional forms of injustice faced by transgender and gender non-conforming persons from oppressed castes, and generated critical media coverage of the issue.

Activists from the Indian trans and gender diverse community were finally able to rupture the mainstream narrative around a potentially harmful policy intervention. As a result, the Bill was not introduced in the Parliament. Yet another potent illustration of the mantra that funds and mobilisation can make change happen.

*Dalits are a caste category that fall outside the four-fold caste system and are known as ‘oppressed castes’ or ‘untouchables’.

This is one of the six stories we have published as CMI! Stories of Change 2021 under the #FundWhatWorks campaign. The stories aim to portray how activists and organisations around the world are working to advance gender justice.

Banner photo: Grace Banu and other activists from Trans Rights Now Collective in India, meeting a member of Parliament with their demands.